Many natural, more sustainable solutions to modern products can be found by looking back in time. I was introduced to one of those solutions while traveling through Aix-en-Provence, France where I discovered Savon de Marseille, a versatile and charming soap tradition. Marseille soap has been in production for over 600 years, and like the sparkling wines of Champagne, it’s unique to the Provence region which surrounds Marseille. Usually sold with labels and certifications stamped directly on its sides instead of on packaging, the light green soap is cut into cubes and made with natural, biodegradable materials.

As we all heighten our hand washing habits right now, this French soap is a fun international item to do so with, but it can also be used for much more. When I visited a soap store in France, I bought a tube-shape block labeled “stick dentifrice.” I asked the saleswoman if it was what my minimal French knowledge thought – toothpaste. “Yes, but it probably won’t taste very good,” she warned. She was right. The soap had less of a minty fresh taste and more of a bitter, lathery sensation. Still, it turned out to be a handy item to have in my travel backpack. I later learned that Marseille soap can clean dishes, be used as a face and body wash, or be mixed with vinegar, baking soda, and water to make laundry detergent. If something needs to be cleaned, you can probably use Marseille soap in a pinch.

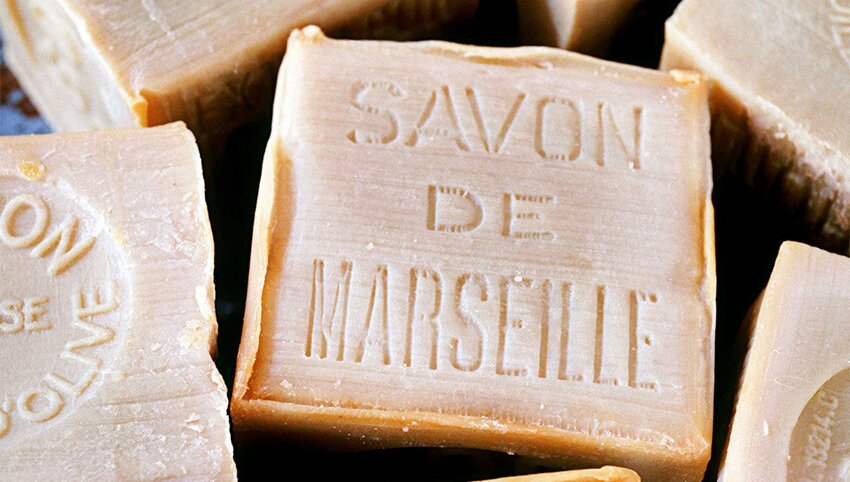

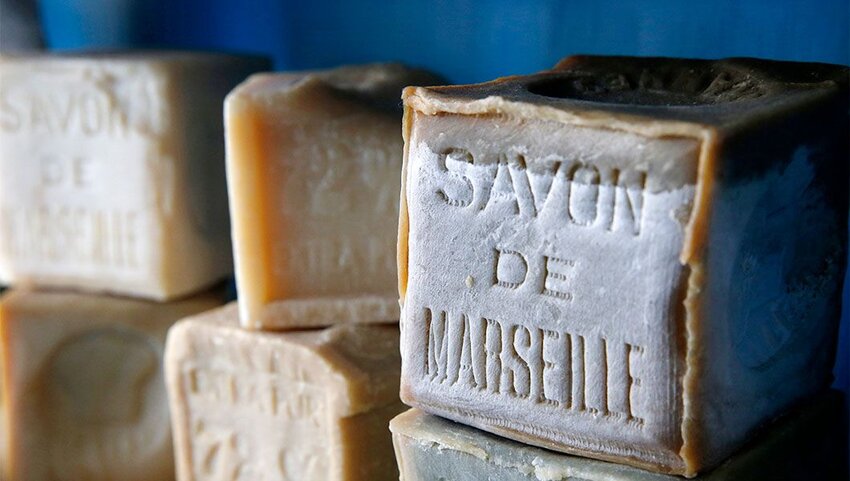

True Marseille soap is unscented and always made with olive oil rather than other vegetable oils, making it hypoallergenic and moisturizing. I remember what it was like to sample it for the first time at that soap store in France. Its blocky shape didn’t slip out of my grip like bar soap tends to, and its delicate foam was soft on my dry hands. As I looked around the walls stacked with rustic, tea green cubes, I found myself surprised that something as utilitarian as soap could be so pretty.

History of Savon de Marseille

Syrian civilizations have been making olive-oil based soaps for thousands of years, and in the 11th century, crusaders brought the soap to Europe. In Spain, the tradition evolved into Castile soap and in France, Marseille soap. The recipe remained similar, and the earliest French soap makers embraced the many natural materials readily available in Marseille and surrounding villages. In the early years of production, olive oil soaps were a luxury item, mostly used by the wealthy across Europe for bathing.

In 1593 the first Marseille soap factory opened and soon, the soap making industry was the economic powerhouse of the area. Thanks to the convenient seaside location, it was traded internationally. In 1688, King Louis XIV decreed a royal edict that regulated what would qualify as “Savon de Marseille,”— soaps had to be made in and around Marseille, heated in cauldrons, made with pure olive oil and excluded animal fats. Any soap maker who tried to flout those rules could be banished.

As soap factories continued to expand, so did the ubiquity of the little green bars. Industrialization made the soap more affordable, and people of all classes began using it for household and personal cleaning. Marseille soap reached its peak in the 20th century when 180,000 tonnes were produced in 1913. But with the rise of synthetic cleaners, Marseille Soap production declined.

Today, there are five soap factories in Marseille and the nearby village Salon, down from 108 in 1924. Still, interest in eco-friendly products has helped renew the tradition in recent years. The advent of COVID-19 also caused some Marseille soap companies to see an increase in sales from locals rather than tourists. Soap maker Serge Bruna told the Associated Press, “People who have lost the habit of using Marseille soap have all of a sudden rediscovered its properties.”

How It’s Made

Making the traditional Marseille soap recipe is a long process. First oil and the alkaline ash from sea plants are boiled together until they are emulsified. This mixture is continuously heated for days at a time to ensure that every last bit of oil is incorporated. After that, the soap maker mixes in saltwater to remove remaining ash, and it continues to boil. Fresh water is later added to remove any impurities, leaving a smooth liquid in the cauldron.

Massive batches of the hot liquid is then poured onto a flat surface where it will take days to cool. It hardens into the signature light green, buttery-textured soap that will be cut into the cubes, stamped, and shipped across the region.

Where to Buy It

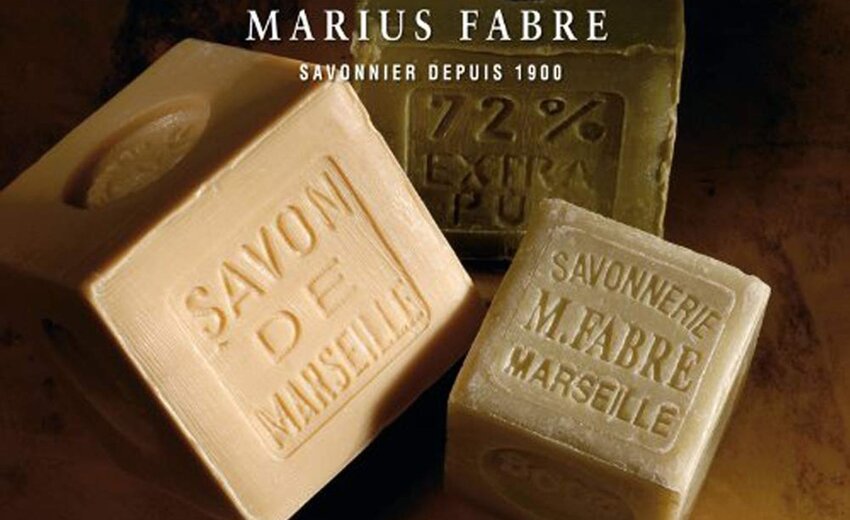

Buy it here: Marseille Soap Marius Fabre | $15

While walking into a soap store and seeing blocks of freshly-scented soap was an incomparable introduction to this product, you can find Marseille soap outside of France. Brands like Rampal Latour and Savon de Marseille ship internationally, and many online stores like Amazon make it incredibly easy to try Marseille soap at home.

Main photo by JARRY/ TRIPELON/ Contributor/ Getty Images